The French legal system

A short guide to the law and legal system in Franc

- Explore France ►

- Essential pages

- Travel in France

- Where to go

- What to see and do

About-France.com

-

the connoisseur's guide to France

| The nature of legal systems | The making of law | How French courts operate |

| The origins of the French legal system | The two branches of French law | Ongoing reforms |

| Getting a lawyer in France |

The

French legal system

1. The nature of legal systems

Unlike English-speaking countries, which use a system of "Common Law", France has a system of "Civil law".

Common law systems are ones that have evolved over the ages, and are largely based on consensus and precedent. Civil law systems are largely based on a Code of Law. Worldwide, Common Law forms the basis of the law in most English-speaking countries, whereas Civil law systems prevail in most of the rest of the world, with the notable exception of many Islamic nations and China.

In line with the democratic principle of the separation of powers, the French judiciary - although its members are state employees - is independent of the legislative authority (government).

2. The origins of the French legal system

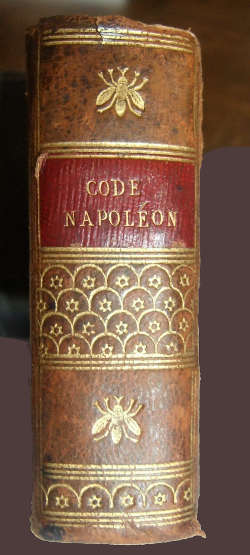

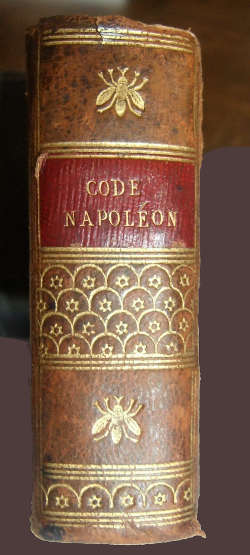

The basis of the French legal system is laid out in a key document originally drawn up in 1804, and known as the Code Civil, or Code Napoléon, (Civil code or Napoleonic code) which laid down the rights and obligations of citizens, and the laws of property, contract, inheritance, etc.. Essentially, it was an adaptation to the needs of nineteenth-century France of the principles of Roman law and customary law. The Code Civil remains the cornerstone of French law to this day, though it has been updated and extended many times to take account of changing society. There are other codes, including notably the Code Pénal, or Penal code, which defines criminal law.3. The making of law

Laws in France, as in other democratic countries, are generally proposed by the Government of the day, and must be passed by the two houses of the French Parliment, the National Assembly and the Senate. They become law as from the date on which they have been passed by Parliament, signed into law by the President, and published in the Journal Officiel, or Official Journal. Statutory instruments (décrets, ordonnances) become law on signing by the minister(s), and being published in the Journal Officiel. Publication in the electronic version of the J.O. is sufficient.4. The two branches of French law

Unlike the English-speaking countries, France has a dual legal system; one branch, known as Droit public, or Public law, defines the principles of operation of the state and public bodies. This law is applied generally through public law courts, known as les Tribunaux administratifs. The other system, known as Droit privé, or private law, applies to private individuals and private bodies.4.1. Private law - le droit privé

This is the basic law of the land. It is administered through the judicial courts.There are two judicial channels, a) those dealing with civil litigation, and b) those dealing with criminal offences

a) Basic civil litigation concerning private individuals is dealt with by a local court, known as a Tribunal d'Instance, or by a regional or departmental court known as a Tribunal de Grande Instance (TGI), depending on the importance of the case. Commercial and business law is administered through institutions known as Tribunaux de commerce. These are known as "first degree courts".

Appeals are heard in a Cour d'Appel or Court of Appeal, a "second degree court". In France, there is a fundamental right of appeal in all cases. In exceptional circumstances, judgements of the Appeal Court can be contested at the highest level, the Cour de Cassation, the French Supreme Court in matters of private law.

b) Everyday offences and petty criminal matters are generally dealt with either by a Juge de proximité (a local magistrate) or a Tribunal de Police (police court); more serious matters will be referred to the Tribunal Correctionnel, the criminal law equivalent of the TGI. The most serious criminal offences, notably murder and rape, will be referred to a Cour d'Assises, or Assize court, where they will tried by jury.

4.2. Public law - le droit public

Complaints or litigation concerning public officials in the exercise of their office are heard in Tribunaux Administratifs, or Administrative Courts. For example, universities or public academic institutions are regularly taken to court over claimed irregularities in the organisation of exams. As in the private law system, appeals can be lodged, in this case with the Cour administratif d'appel, or Administrative appeals court. The highest echelon, the Supreme Court for public law, is the Conseil d'Etat, or Council of State, the body ultimately responsible for determining the legality of administrative measures.5. How the courts operate in France

French courts are presided over by Juges (Judges) also known as Magistrats (magistrates). Magistrats, are highly qualified professionals, almost all of whom have graduated from the postgraduate School of Magistrature; they are high-ranking juges . In other words, a French Magistrat is not at all the same as a Magistrate in the English legal system.Criminal court proceedings can be overseen by a juge d'instruction. The judge who is appointed to the case is in charge of preparing the case and assessing whether it should come to court. In legal jargon, this system is known as inquisitorial, as opposed to the adversarial system used in Common Law legal systems.

In court, the judge or judges arbirate between the the prosecution and the defence, both of which are generally represented by their lawyers, or avocats. The French judicial system does not have recourse to juries except in assize courts.

If the case goes to appeal, the arguments of the prosecution and the defence are taken over by appeals specialists known as Avoués.

6. Recent reforms

In 2008, President Sarkozy announced plans to further reform and streamline the French judiciary. Among the reforms were plans to reduce the number of courts, move court procedures towards a more adversarial system, and to get rid of the system of avoués in the courts of appeal. This change has not yet been implemented.One reform recently tried out in a couple of Tribunaux correctionnels (criminal courts) was the introduction of trial by jury, previously limited to the assize courts. Juries in this case were made up of six members of the public, and three magistrates. But in 2013, the socialist administration of François Hollande decided to scrap this reform, claiming the process was expensive, slowed down the judicial procedure, and did not produce any significant change in results.

7. Getting a lawyer in France

If you wish to take legal action against someone or against an institution, if someone is taking legal action against you (civil litigation), or if criminal charges have been brought against you (for example for reckless driving), you may need to find a lawyer (trouver un avocat)..The consular services of the British, United States and other embassies in Paris, and consulates in other cities, can often point you in the direction of an English-speaking lawyer. There are a number of English-speaking lawyers practicing in France, including British and American lawyers, qualified to practise as lawyers in France; though they are not to be found in every town or city, far from it. To find one, check the local yellow pages, or contact the local Tribunal d'Instance.

Alternatively, contact a local French lawyer specialising in the appropriate field of law : family law, inheritance law, property law, etc. In the end, proximity and competence are usually more important than having an English-speaking lawyer; after all, your lawyer will be pleading in a French court. And many French lawyers do have a basic ability to speak English.

For companies, the situation is easier, and there are growing numbers of international corporate law firms, including some very big ones, established in Paris, Lyon, Toulouse and other big cities. For details contact the local consulate, the Tribunal de commerce, or the Chamber of Commerce. The Franco-British chamber of commerce has a list of a number of international business law firms in France.

Legal Aid

Legal aid is easier to obtain, and cheaper, in France than in many other countries. A useful first port of call for anyone wanting legal aid is the Maison de Justice, usually attached to the local Tribunal d'Instance.With contributions from Dr. Audrey Guinchard, Dept. of Law, University of Essex

About-France.com

Home

page - Site search

- Regions

- Maps of France

A short guide to French law. Law

practitioners and law students need to be aware that the

French legal system, based on a code of law, is in many ways

substantially different to the "common law" legal systems practiced in

the English-speaking countries. That being said, the object of the

legal system in France is the same as the object of the legal systems

used elsewhere in the world, and that is to provide justice to citizens

and uphold the aw of the land.

The Code Napoléon, the backbone of French law.

The separation of church and state was enacted in 1905, putting the law solely in the hands of the judiciary.

Shopping

from

France,

fashion, souvenirs,

food and wine and

more.

Shopping

from

France,

fashion, souvenirs,

food and wine and

more.

Writers, academics, discover the scope and technique of self publishing on Academic Self Publishing.com

Photos - public domain

The Code Napoléon, the backbone of French law.

The separation of church and state was enacted in 1905, putting the law solely in the hands of the judiciary.

A choice of French

stores & brands that deliver abroad

Self publishing for academics

Self-publishing is the new and free way to publish academic books or ebooks that can reach a worldwide audienceWriters, academics, discover the scope and technique of self publishing on Academic Self Publishing.com

Photos - public domain