Art in the Grand Siècle and the Age of Enlightenment

A short history of French Art - 3.

About-France.com

- the connoisseur's guide to France

Art in France 1590 - 1790 - from classical baroque to French rococo

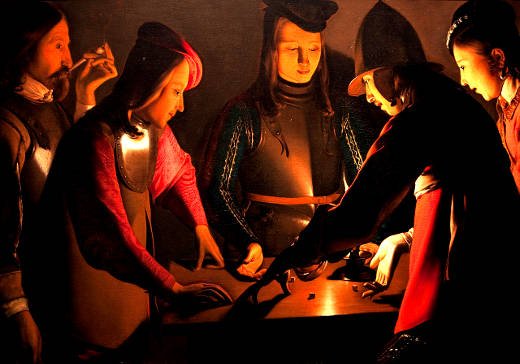

Georges de Latour - Dice players - Preston Hall museum - Stockton

Baroque was not a break from Renaissance classicism, it was a development. At the time, artists and architects whom we today think of as being the masters of Italian baroque art saw themselves as painting and working in a new phase of classicism, one that emphasised emotions, apprehension, movement and vitality. Baroque was a new classicism exaggerated by intense light and shadow, dramatic perspecitves, and a sometimes exuberant use of colour.

Seeing baroque art as a permutation of classicism sometimes requires a leap of faith when one looks at the works of great baroque artists of Italy, Flanders or Spain - such as Caravaggio, Rubens or Zurbarán. By contrast, much of French baroque is altogether more clearly classical, with less of the effusion seen in other parts of Europe, remaining more "classic" and subdued in its development of the idiom of Renaissance art.

The adjective "Baroque" even seems misplaced when used to describe the works of some of the greatest French artists of the seventeenth century, notably Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin; but it sits well with two important artists who were contemporaries of Caravaggio, George de Latour and Philippe de Champaigne.

Sometime called "the French Caravaggio", Latour (1593-1652) who came from Lorraine, specialised in paintings, mostly small canvasses showing intimate candle-lit scenes with intense light and shade. By contrast, Philippe de Champaigne, born in Brussels in 1602, worked for most of his life in Paris, where he was called upon to paint many large religious paintings as well as portraits including several of Cardinal Mazarin. His paintings on religious subjects, particularly when relating to death show all the intensity of emotion that tends to characterise baroque art.

Nicolas Poussin - The Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth & John the Baptist - St. Petersburg - the Hermitage

Poussin evolved his own theories of painting, notably his idea of the grande manière, the view that a work of art must narrate a story in the clearest possible manner, without confusing the issue with too much distracting detail. In this way, his art distinguishes itself from mainstream baroque art in which a profusion of detail often distracts singularly from the main theme.

Poussin's contemporary, Claude Lorrain (1600-1682), was a very different kind of artist, and one whose works were to inspire a whole following of neoclassical painters. For the record, it is useful to realise that Claude Lorrain goes under several different names: born in 1600 in Lorraine, and known from birth as Claude Gellée, he became known in the art world as just Claude, or Claude le Lorrain (Claude from Lorraine). In French he is often referred to as Le Lorrain.

Claude Lorrain - Pastoral scene with classical ruins. Grenoble - Musée des Beaux Arts

With the two greatest French artists of their time working in Rome, patrons in France looking for portraits or works of art for churches, chapels and châteaux used the services of a large number of less remembered artists, painting often with considerable skill but as followers, rather than innovators, in the field of art. Two names stand out from the rest, Charles Le Brun and Hyacinthe Rigaud.

Charles Le Brun (1619 - 1690), who studied in Rome under Poussin, was considered by King Louis XIV to be the greatest French painter of all time, and was commissioned by him for monumental works and ceilings in his palaces at the Louvre and Versailles. Le Brun also worked for other patrons on projects in various châteaux, such as Vaux le Vicomte, where his works can still be seen today.

Le Brun was also one of the key movers in the struggle to get official recognition for the best artists in France, an idea that eventually led King Louis XIV to set up, in January 1848, the first French Royal Academy of painting and sculpture. From then on, the country's greatest artists would get official acknowledgement, making the Academy the official arbiter of good art.

Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659 - 1743) was the great portrait painter of the Grand Siècle, and the portraits he painted during the second half of the 17th century have determined the way that people see or imagine the great and the famous who gravitated around the Sun KIng during this period of absolutist monarchy in France.

The influence of Louis XIV on art in his age cannot be underestimated. If the second part of the 17th century was not a great period of innovation in French art, this was in no small degree due to the role played by the King and his court as arbiters of fashion, style and art. Artists who wished to make their way in life knew that to do so they had to follow in the path of Le Brun or Rigaud, painting portraits for the wealthy and decorating their houses and churches with suitably ornate canvasses and murals in the style of the age. It was not until the start of the 18th century that things began to change.

The harbinger of change was Antoine Watteau (1684 - 1721). Born in Valenciennes, a town on the border with Flanders, Watteau first found work as an artist in Paris painting copies of Flemish genre paintings for bourgeois customers. Later he became a genre painter in his own right, specialising in theatrical scenes. His depictions of staged rural scenes are very different from the rural scenes painted by Claude Lorrain; and while the landscape element is remains important in Watteau's work, it is the people who are the main subject. With Watteau, French art began the move from the grandeur of baroque art towards the smaller-scale and more intimate style known as rococo.

A contemporary of Watteau, and another genre painter though not at all in the same genre, was Jean Siméon Chardin (1699 - 1779). Chardin was strongly influenced by Dutch genre painting which had become popular throughout Europe, as the new middle classes and expanding aristocracy sought and commissioned works of art to decorate their houses. Chardin's art is neither baroque nor rococo nor classical; it echoes the work of painters like Vermeer or Pieter de Hooch, taking its inspiration from northern Europe, not Italy, from everyday life and ordinary people, not from great moments in history, religion or mythology. Chardin painted still life scenes, domestic scenes and portraits of ordinary people, and in doing so helped to move French art in a new direction that was to inspire many French artists for over a century. Both Manet and Cézanne recognised the influence of Chardin on their own art.

Yet while French art, with Chardin, was moving into new territory beyond the influence of the baroque, other artists were following Watteau; foremost among these was these Paris-born artist François Boucher (1703 - 1770) who even in his time was recognised as the master of rococo art.

A prolific artist, Boucher was both painter and engraver, as well as a designer of tapestries. After being admitted to the French Royal Academy in 1731, he was much in demand as a portrait painter, and received numerous commissions from Royal and aristocratic patrons, most notably from Madame de Pompadour of whom he painted a number of portraits.

Boucher painted in a style less delicate than Watteau, and his work is much more thematically diverse. He painted genre scenes, portraits, religious paintings, classical scenes and even chinoiseries, introducing into French art a new sensuality that owes something both to Rubens and Tiepolo. While his portraits of Madame de Pompadour, Louis XV's favourite mistress, are fully clothed, Boucher excelled in nudes variously portrayed as Venus, Diana or other mythological beauties.

His bold use of colour - far less discreet than Watteau - was an inspiration to many younger artists but displeased the first great French art critic, Diderot, who wrote of one of his paintings on show at the 1763 Salon : "This man is the ruin of all young aspiring painters. Hardly do they know how to hold a brush and a palette than they are torturing themselves with garlands of children, painting podgy vermillion backsides, and throwing themselves into all manner of extravagances that are not compensated for by warmth, nor by originality, nor by kindness, nor by the magic of their model: they just imitate his mistakes."

While Diderot was critical of Boucher partly on moral grounds, he enthused about another younger painter, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725 - 1805). Greuze came to popularity as a genre painter in the manner of Chardin, specialising in sentimental portraits and scenes with a moral, which went down well with Diderot and were well in keeping with the spirit of the age.

Greuze's moralizing scenes, with their stylized poses and classic movements, also prefigure the great heroic works of the up and coming generation of neoclassicists, notably David and Gérard, who would take moralising art onto a new plane, out of the intimacy of the family scene and small genre painting, and onto the vast canvases of the Imperial age that was soon to dawn

By the 1770s however, Greuze had fallen out with the Academy, and became something of an independent painter and engraver, popular with the people, no longer with the establishment – a popularity that doubtless helped him to come through the French Revolution unscathed.

Classic late rococo : the Swing, by Fragonard - 1767.

London - the Wallace collection

After a period when he worked essentially on history paintings, interpreted with the lightness of his rococo touch, Fragonard later became known – and is today essentially remembered – as the painter of frivolity, painting scenes of the aristocracy at leasure in idealised gardens or parkland, or at home with their children. As such he was in much demand as long as the aristocracy continued to enjoy their privileged lifestyle; but that was not to be for long.

By 1785, rococo as a genre had run its course, and enlightened France was heading for the dramatic events of 1789 which would profoundly impact not just the way the country was organised, but almost averything about French life and culture too. While revolutionary France would have a place for historic art, for some forms of genre art, and for art with a moral, it would have no place for the frivolity of rococo, so intimately linked to the lifestyles and tastes of the Ancien Regime. And though Fragonard as a man survived the Revolution, Fragonard the artist did not. It would be a generation or more before any later French artists would recognise any kind of historic debt to Watteau, Boucher or Fragonard.

The About-France.com history of art in France :

- Art and architecture in Medieval France

- French art in the Renaissance

- French art from Baroque to Rococo - 1590 - 1790

- Neoclassicism and Romanticism

- Naturalism and realism - landscape and life in 19th century French art

- Impressionism

- Post- Impressionism - from Pointillism to Cubism

Website

copyright © About-France.com 2003 - 2025

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

About-France.com

Home

page - Site

search

- Regions

- Maps of France

- Contact

Photo top of page : Claude Lorrain - The

Judgement of Paris - Washington, National Gallery of Art.

Philippe de Champaigne - The repentant Mary Magdalene.. Houston Art gallery

Ceiling panel in the Hall of Mirrors in the Château de Versailles - by Charles le Brun

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

Watteau : Mezzetino - a character from the Commedia dell'Arte.

Metropolitan Museum - New York

Boucher : portrait of Madame de Pompadour.

Alte Pinakothek - Munich

Greuze : The father's curse - detail.

The Louvre - Paris

About-France.com is a fully independent website affiliated to certain online booking platforms, and may receive a small commission only on bookings made through affiliate sites . This has no effect at all on the price paid by the visitor.

Copyright texts © About-France.com

French art from 1590 to

1790

The beginnings of modern France. French art in the Grand Siècle and the age of Enlightenment - the Bourbon age, from from Henri IV to the French Revolution

The beginnings of modern France. French art in the Grand Siècle and the age of Enlightenment - the Bourbon age, from from Henri IV to the French Revolution

Philippe de Champaigne - The repentant Mary Magdalene.. Houston Art gallery

Ceiling panel in the Hall of Mirrors in the Château de Versailles - by Charles le Brun

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

Watteau : Mezzetino - a character from the Commedia dell'Arte.

Metropolitan Museum - New York

Boucher : portrait of Madame de Pompadour.

Alte Pinakothek - Munich

Greuze : The father's curse - detail.

The Louvre - Paris

| ►► Site guide |

| About-France.com home |

| Full site index |

| About-France.com site search |

| ►► Principal chapters on About-France.com : |

| Guide

to the

regions of France Beyond

Paris, a guide to the French regions and their tourist attractions.

|

| Guide

to Paris Make

the most of your trip to Paris; Information on attractions, Paris

hotels, transport, and lots more.

|

| Accommodation

in France

The different options, including hotels,

holiday gites, b&b, hostels and more

|

| Tourism

in France

The

main tourist attractions and places to visit in France - historic

monuments, art galleries, seasides, and more

|

| Planning

a trip to France

Information

on things to do before starting your trip to France.

|

| Driving

in France

Tips

and useful information on driving in and through France - motorways,

tolls, where to stay....

|

| Maps

of France

Cities,

towns, departments, regions, climate, wine areas and other themes.

|

| The

French way of

life

A mine of information about

life and living in France, including

working in France, living in France, food and eating, education,

shopping.

|

| A-Z

dictionary of France Encyclopedic

dictionary of modern France - key figures, institutions, acronyms,

culture, icons, etc.

|

| ►► More accommodation |

| Gites in France |

| Bed & breakfast in France |

| Small rural campsites |

| Small hotels in France |

About-France.com is a fully independent website affiliated to certain online booking platforms, and may receive a small commission only on bookings made through affiliate sites . This has no effect at all on the price paid by the visitor.

Click here for

low-cost car hire in France

low-cost car hire in France

Copyright texts © About-France.com