Naturalism and realism - landscape and life

A short history of French Art - 5.

About-France.com

- the connoisseur's guide to France

1820 - 1890 - Towards a redefinition of painting

Terminology: In

English, the term naturalism

is widely used to refer to landscape art painted directly from nature,

without idealisation and without moral judgement. In French le naturalisme is

used more narrowly to refer to an artistic and literary movement in the

later 19th century exemplified in the paintings of

Bastien-Lepage and the novels of Zola or Flaubert.

The origins of landscape painting

Claude Lorrain - Pastoral scene with classical ruins. Grenoble - Musée des Beaux Arts

By the seventeenth century, as painters began to get more commissions from civil rather than religious patrons, landscape took on an ever increasing importance. Religious orders commissioned art to celebrate saints or tell stories from the scriptures. Civil patrons commissioned art to tell a story, for portraiture, or just for decoration.

Thus whereas in the past, landscapes had been incidental backgrounds to pictures that told a story, religious, moral or historic, from the 17th century onwards, with some painters such as Claude Lorrain in France, the roles were reversed. With Claude, religious or mythological stories became the incidental pretext for paintings that were essentially landscapes, or even seascapes; and indeed in some paintings, the landscape became the topic of the painting itself, not the setting for a story.

Yet with Claude Lorrain and French landscape artists of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, landscape, le paysage, did not mean realism. The landscapes of Claude, or of Poussin or Lancret or Claude-Joseph Vernet, were idealised places, inspired by nature, not painted from nature. Landscapes were mostly imaginary, and if they were inspired by real places, the places they depicted were often not mentioned.

This was even the case with the Dutch landscape "genre painters" such as Hobbema or Ruysdael, who specialised in landscape scenes that were close to the lives of people in the Netherlands; sometimes they would paint scenes of places, such as Hobbema's well-known Avenue at Middelharnis; but more often they would paint works entitled "landscape" or "watermill", in which the location, even if painted from life, was not indicated..

John Constable - Flatford Mill (Tate Gallery, London). The influence of Constable on French landscape art cannot be underestimated

And with the new generation of landscape artists, the location was frequently - though by no means always - announced in the title of the painting: Flatford Mill, or Wivenhoe Park, or Petworth House, for example : real places, not imaginary ones.

Landscape painting in France - the Barbizon school

Théodore Rousseau - Landscape with trees

The "Barbizon school" was to dominate French landscape art for half a century, bringing together most of France's finest landscape artists of the mid nineteenth century. Two pioneering artists of the time, Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet, even moved to live in Barbizon, where they would regularly have visits from Corot, Diaz, Huet and many others. Even artists like Gustave Courbet would put in an appearance from time to time.

Yet while Courbet was a landscape artist, and one who painted out in the open air, his style was rather different to those of the Barbizon artists.

Corot : the Hay cart

Millet, Courbet and realism

Jean-François Millet - The gleaners . Paris, Musée d'Orsay

Gustave Courbet - the Stone breakers. Courbet shows the reality of working life, against the backdrop of a scene from his native Jura mountains.

As landscape artists they would often put nature - cliffs, stags, waterfalls - at the heart of their works. Indeed, both Courbet and Millet painted landscapes without any human activity; but even in paintings without any human figures, there is no idealising of nature. It is real, and sometimes dark and menacing.

After all, at a time when the large majority of the population of France still lived a rural life and tilled the land, nature, the outdoors, was primarily a workplace, not a place for leisure. Life was outdoors, so was death, as in Courbet's iconic open-air Burial at Ornans; and in his portrayal of human life and death, as in other ways, Courbet was a revolutionary.

Landscape naturalism and realism were part of the same continuum, and there was no clear-cut dividing line between them. Indeed the terms are regularly confused; yet the Realists, most importantly Courbet, Millet and Honoré Daumier, were not just landscape artists. Even if Millet's masterpieces les Glaneuses (the Gleaners) or l'Angélus, as many of Courbet's greatest works, use the landscape as a background, the Realists were more than just landscape genre painters. Their range of subject matter was far wider.

.

Courbet's 1855 Realist manifesto did not go down well in all quarters, quite the contrary. In the mid 19th century, the majority of French artists were still painting according to the canons of academic art, in styles that idealised both humans and scenery. The struggle between classicism and romanticism

Edouard Manet - The game of croquet - Stadel Museum, Frankfurt. The dark landscape background has echos of the Barbizon school; but the brushwork is Impressionist

Yet others could. A young up and coming realist who greatly admired Courbet, was Edouard Manet. Best known today as one of the Impressionists, Manet was more exactly a realist who was greatly admired by the younger Impressionists, but never actually exhibited in the Impressionist exhibitions

Through this lineage, Courbet and Manet have come to be recognised as the founding fathers of modern art.

Many French 19th century artists were prolific producers - Courbet and Corot among them - and most provincial museums in France have a representative display of art from this period. Major works by Courbet are on display in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Besançon, and nearby in the Courbet Museum in Ornans, the small town in Franche-Comté where he was born.

The finest overall collection of French naturalist and realist art can be seen in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris,.

The About-France.com history of art in France:

- Art and architecture in Medieval France

- French art in the Renaissance

- From Baroque to Rococo - the Grand Siècle and the Age of Enlightenment

- French art in the age of Revolution Neoclassicism to Romanticism

- Naturalism and realism

- Impressionism

- Post-

Impressionism - from

Pointillism to Cubism

Website

copyright © About-France.com 2003 - 2025

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

About-France.com

Home

page - Site

search

- Regions

- Maps of France

- Contact

Photo top of page : Gustave Courbet - The Wave

- Le Havre, Musée Malraux.

17th century Dutch landscape genre painting.

From a painting by Salomon van Ruysdael

The old windmill near Barbizon - by Narcisse Diaz de la Peña

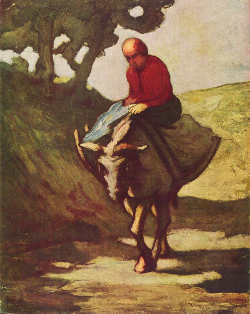

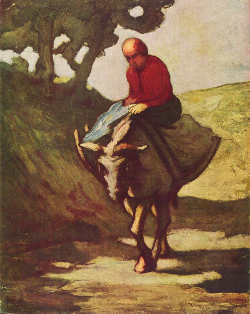

Man on a donkey - by Honoré Daumier

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

About-France.com is a fully independent website affiliated to certain online booking platforms, and may receive a small commission only on bookings made through affiliate sites . This has no effect at all on the price paid by the visitor.

Copyright texts © About-France.com

The new art - 1820 - 1890

While most French artists of the time remained academic and strugged with the conflict between classicsm and romanticism, some were breaking away from the traditional constraints, taking art out of the studio and into the open air. Landscape art had reached France, and out of French landscape art grew something even more important for the subsequent history of art, not just in France but worldwide. Realism

While most French artists of the time remained academic and strugged with the conflict between classicsm and romanticism, some were breaking away from the traditional constraints, taking art out of the studio and into the open air. Landscape art had reached France, and out of French landscape art grew something even more important for the subsequent history of art, not just in France but worldwide. Realism

17th century Dutch landscape genre painting.

From a painting by Salomon van Ruysdael

| ►► Site guide |

| About-France.com home |

| Full site index |

| About-France.com site search |

| ►► Principal chapters on About-France.com : |

| Guide

to the

regions of France Beyond

Paris, a guide to the French regions and their tourist attractions.

|

| Guide

to Paris Make

the most of your trip to Paris; Information on attractions, Paris

hotels, transport, and lots more.

|

| Accommodation

in France

The different options, including hotels,

holiday gites, b&b, hostels and more

|

| Tourism

in France

The

main tourist attractions and places to visit in France - historic

monuments, art galleries, seasides, and more

|

| Planning

a trip to France

Information

on things to do before starting your trip to France.

|

| Driving

in France

Tips

and useful information on driving in and through France - motorways,

tolls, where to stay....

|

| Maps

of France

Cities,

towns, departments, regions, climate, wine areas and other themes.

|

| The

French way of

life

A mine of information about

life and living in France, including

working in France, living in France, food and eating, education,

shopping.

|

| A-Z

dictionary of France Encyclopedic

dictionary of modern France - key figures, institutions, acronyms,

culture, icons, etc.

|

| ►► More accommodation |

| Gites in France |

| Bed & breakfast in France |

| Small rural campsites |

| Small hotels in France |

The old windmill near Barbizon - by Narcisse Diaz de la Peña

Man on a donkey - by Honoré Daumier

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

About-France.com is a fully independent website affiliated to certain online booking platforms, and may receive a small commission only on bookings made through affiliate sites . This has no effect at all on the price paid by the visitor.

Click here for

low-cost car hire in France

low-cost car hire in France

Copyright texts © About-France.com