From Neoclassicism to Romanticism

A short history of French Art - 4.

About-France.com

- the connoisseur's guide to France

1760 - 1840 - The revolutionary age in French art

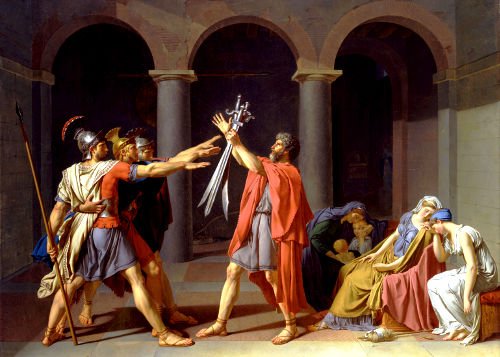

David - the Oath of the Horatii - Louvre, Paris

Since the early 17th century, French art had evolved between the baroque and rococco, and the academic and classical. Sevententh century "Classicism", as exemplified by the works of Claude Lorrain, was essentially an aesthetic movement. It took the mythology and stories of the ancient world, and used and embellished them to create an idealised pictorial world.

Nanine Vallain - Liberty - 1793. Paris, Louvre

As an architectural style Neoclassicism evolved in France in the early 18th century; but it was not until after 1760 that it took a hold in the visual arts, notably as a reaction to the perceived frivolity and decadence of baroque and rococco painting. Its leading figures were the artistic elite of France during the age of Revolution, and the turmoil that ensued as the Republic became the Consulate, then the Empire until the monarchy was restored in 1814.

While French neoclassical art is finely represented in the works of a number of painters, two stand out in particular. Jacques-Louis David, sometimes called the master of the neoclassical school in France, and his pupil Jean Auguste Ingres. David, who was trained in the classical tradition, studied in Rome before returning to Paris. His monumental painting the Oath of the Horatii (Paris, Louvre), with its severity and geometric precision, is generally considered as the archetypal work of French Neoclassicism. Elected to the French parliament after the Revolution, David reigned over art in France, establishing Neoclassicism as a kind of official style of the French Revolution. Another of his most famous paintings is the Death of Marat, one of the revolutionary leaders of France, also in the Louvre.

After Napoleon came to power in 1804, David became a fervent Bonapartist and Neoclassicism became even more closely associated with the styles of the "Empire" than it had with the first Republic. His huge canvases glorifying Napoleon are among the more remarkable works that today hang in the Louvre. But he was not the only one to glorify the Emperor.

Detail from Napoleon at Austerlitz, by François Gérard. Palace of Versailles

Among David's pupils were Gros and Gérard, several of whose monumental paintings can also be seen in the Louvre and other French museums. But the second great master of Neoclassicism was Ingres, whose work is generally on a smaller scale, and more refined. Ingres is best remembered for his portraits.

Princesse de Broglie, by Ingres.

Metropolitan Museum of New York

Romanticism was all about mood and feeling, drama and emotions, not about precision or perfection. As a movement, it had begun at the start of the "Gothic" revival in England, then in Germany, in the mid 18th century. At a time when Neoclassicism was reigning supreme in Imperial France, artists like Turner in England and Caspar David Friedrich in Germany were producing a radically different kind of art. One of the first to move across the divide in France was Thédore Géricault. His massive Radeau de la Méduse, a historical tableau comparable is size and object to the great works of Gros and Gérard, is altogether different in theme and emotions. It depicts not some heroic event in contemporary French history, but the aftermath of a shipwreck, with the survivors calling out for help.

The Raft of the Méduse, by Theodore Géricault. Paris, Louvre

But if Géricault was the precursor, the artist who rapidly established himself as the figurehead of French romantic art was Eugéne Delacroix, born 1798. By the mid 1820s, the battle between the "classicists" and the "romantics" was firmly engaged. Neoclassicism was by then the art of the establishment, academic and institutional, Romanticism was the art of the innovators. It was a pop revolution. For the next three decades, France was the cultural battleground between the traditionalists and the innovators.

Delacroix's iconic Liberty leading the People, celebrating the second French Revolution of 1830, is totally different from the neoclassic depiction of Liberty painted by Vallain in 1793.. Romanticism blossomed with Delacroix in art, with Baudelaire and Victor Hugo in literature and Berlioz in music - to name but four; and by the middle of the nineteenth century it had won the day.

Liberty

leading the People, by Delacroix. Paris, Louvre

Liberty

leading the People, by Delacroix. Paris, LouvreFew people today have even heard of the institutional painters of mid-19th century France; but Delacroix, who sought inspiration in emotionally charged scenes and exotic landscapes, served as an inspiration to others who took art into new territory in form and subject-matter. Though Delacroix did not teach pupils, his work was widely admired by the innovators in French art, including later Romantics like Fantin Latour, Naturalists like Courbet, and virtually all of the Impressionists.

Where to see art from the Age of Revolution

Paris: the Louvre (particularly for 18th century) and the Musée d'Orsay (for 19th century)

Paris: Musée Delacroix (in the Latin quarter)

Montauban : Musée Ingres

The About-France.com history of art in France :

- Art and architecture in Medieval France

- French art in the Renaissance

- French art from Baroque to Rococo - 1590 - 1790

- Neoclassicism and Romanticism

- Naturalism and realism - landscape and life in 19th century French art

- Impressionism

- Post-

Impressionism - from

Pointillism to Cubism

Website

copyright © About-France.com 2003 - 2025

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

Photos: all photos on this page are in the public domain.

About-France.com

Home

page - Site

search

- Regions

- Maps of France

- Contact

Photo top of page : Eugène Delacroix

- from La

mort de Sardanaple. Paris, Louvre.

David - the Death of Marat. Paris, Louvre

Napoleon, by Ingres. Paris, Musée des Invalides

About-France.com is a fully independent website affiliated to certain online booking platforms, and may receive a small commission only on bookings made through affiliate sites . This has no effect at all on the price paid by the visitor.

Copyright texts © About-France.com

The period from 1760 to

1840

saw massive changes in France and Europe, and they were not just political. In art, this was the start of the modern era as artists moved from copying from the past to developing new ways

saw massive changes in France and Europe, and they were not just political. In art, this was the start of the modern era as artists moved from copying from the past to developing new ways

David - the Death of Marat. Paris, Louvre

Napoleon, by Ingres. Paris, Musée des Invalides

| ►► Site guide |

| About-France.com home |

| Full site index |

| About-France.com site search |

| ►► Principal chapters on About-France.com : |

| Guide

to the

regions of France Beyond

Paris, a guide to the French regions and their tourist attractions.

|

| Guide

to Paris Make

the most of your trip to Paris; Information on attractions, Paris

hotels, transport, and lots more.

|

| Accommodation

in France

The different options, including hotels,

holiday gites, b&b, hostels and more

|

| Tourism

in France

The

main tourist attractions and places to visit in France - historic

monuments, art galleries, seasides, and more

|

| Planning

a trip to France

Information

on things to do before starting your trip to France.

|

| Driving

in France

Tips

and useful information on driving in and through France - motorways,

tolls, where to stay....

|

| Maps

of France

Cities,

towns, departments, regions, climate, wine areas and other themes.

|

| The

French way of

life

A mine of information about

life and living in France, including

working in France, living in France, food and eating, education,

shopping.

|

| A-Z

dictionary of France Encyclopedic

dictionary of modern

|

About-France.com is a fully independent website affiliated to certain online booking platforms, and may receive a small commission only on bookings made through affiliate sites . This has no effect at all on the price paid by the visitor.

Click here for

low-cost car hire in France

low-cost car hire in France

Copyright texts © About-France.com